Dealer in Rare and First-Edition Books: Western Americana; Mystery, Detective, and Espionage Fiction

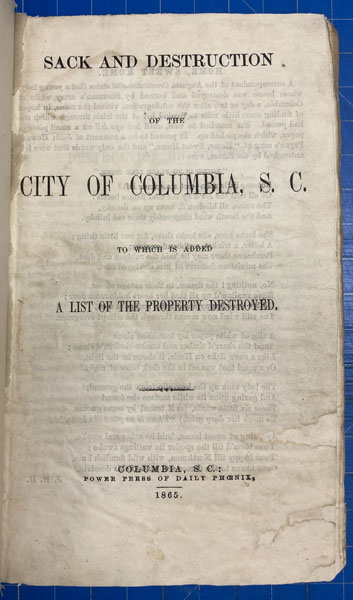

Sack And Destruction Of The City Of Columbia, S.C. To Which Is Added A List Of The Property Destroyed

Simms, William Gilmore

Other works by Simms, William GilmorePublication: Power Press of Daily Phoenix, 1865, Columbia, SC

First edition. 8" x 5 1/4" plain brown wrappers. 76pp. A narrative recounting of William Tecumseh Sherman's entry into and occupation of Columbia, South Carolina's capital city, and its subsequent destruction in the waning days of the Civil War. Simms originally published Sack and Destruction serially in The Columbia Phoenix, a small newspaper edited by Simms that commenced publication in the waning weeks of the Confederacy' from the newspaper's first edition until 10 April 1865. After the close of the War, Simms edited and revised these serialized pieces into pamphlet form, publishing it in October of that year. "William Gilmore Simms (1806-1870), a native South Carolinian and one of the nation's foremost men of letters, was in Columbia and witnessed firsthand the city's capture and destruction. A renowned novelist and poet, who was also an experienced journalist and historian, Simms deftly recorded the events of February 1865 in a series of eyewitness accounts. "By 1865 Columbia was one of the few places of refuge for Confederates fleeing the Union onslaught across the South. It also retained a vital importance to the war effort, serving as a nexus for one of the last rail systems that could still get supplies to Gen. Robert E. Lee's beleaguered forces in Virginia. It was a production center, too: The city produced swords, rifles, shoes, socks and uniforms; the Palmetto Iron Works manufactured shells, minie bullets and cannon. Joseph LeConte, a chemistry professor at South Carolina College, provided indispensable war service by heading efforts to produce badly needed medicine and gunpowder. In early January, Sherman, encamped at Savannah, Ga., decided to take Columbia during his planned march through the Carolinas. After sweeping aside the token resistance met along the way, Sherman's troops arrived at the southern edge of Columbia on the morning of Feb. 17. They drove off a handful of Confederate skirmishers, circled around the city and entered it in force from the northwest. What the soldiers found was a city almost ideally situated to burn. Columbia was bursting with highly flammable bales of cotton. Its location made it ideal for cotton trading and transport, and overproduction during the war as well as the Union blockade resulted in tremendous amounts of cotton being stored in all available warehouses, basements and empty buildings. To keep the cotton out of Union hands, on Feb. 14, Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard, who headed the defense of Columbia, ordered that the stored cotton be taken outside the city and burned. But there was too much cotton to move by carriage, so the Confederate officer in charge of the operation decided to move the bales into city streets, to be burned there. His order was published in Columbia's newspapers on Feb. 15. But early on Feb. 17, mere hours before Union soldiers entered Columbia, Beauregard's subordinate Wade Hampton persuaded him to reverse the order, out of concern that the flames of burning cotton in the streets might spread throughout the city. Around 7 a.m. Hampton issued an order not to fire the cotton, but it was too late. The Confederate withdrawal, then underway, was confused and chaotic. The chain of command had broken down, so the order was at best fitfully communicated to soldiers remaining in the city and private citizens. By the night of Feb. 16-17, before any Union soldiers entered the city, cotton was already burning. In at least two places witnesses saw cotton burning in Columbia, including on Richardson Street, the city's central cotton market. It's unclear whether these fires were started by looters in a city where order had dissolved, by soldiers following Beauregard's order or by Union shelling. Nevertheless, by 3 a.m., as one Confederate officer recalled, 'The city was illuminated with burning cotton.' Besides cotton, Columbia held a remarkable amount of alcohol. Since early in the war, Charleston merchants had shipped in vast stores of whiskey to save it from naval bombardment. Columbia also had a government distillery that produced several hundred gallons of whiskey a day, and a large quantity of medicinal supplies had been abandoned and left unguarded in the confusion. As soon as Sherman's soldiers entered Columbia and began to march down Richardson Street, jubilant blacks and placating whites plied them with whiskey. This went on over the next several hours as unit after unit paraded through Columbia and then took up camp north and east of the city. But this army wasn't the greatest threat that came in from the north. Since before dawn on the 17th, a strong wind had blown into the city. Around noon Sherman rode down Richardson Street and took note of the scene. Cotton bales were torn open. The wind had scattered the cotton thickly, catching it on buildings and tree branches. Sherman remarked that the result was like a Northern snowstorm. Southern witnesses agreed. The Columbian Mary S. Whilden, for example, noted the city's 'peculiar appearance' from streets and trees being covered with the 'most combustible material.' Still, by mid afternoon, relative calm had returned to Columbia. Union guards had been posted at major intersections, in front of public buildings and at private homes that requested protection. Sherman told the mayor that the burning of war-related buildings would be delayed because of the high winds still blowing through the city. Federal troops worked with Columbia's fire department to control a few fires that had somehow broken out. Sherman appropriately assigned Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard provost duty command, and Howard resolved to remain in Columbia to keep a close eye on things. As evening came on, though, the situation quickly deteriorated. Encamped troops had been straggling back into Columbia, seeking amusement and more of the easily available alcohol. Both soldiers and citizens were getting drunk and rowdy. Some Union officers ordered whiskey barrels to be smashed to keep them out of the crowd's hands, but no one paid them much mind. Howard ordered a fresh contingent of troops into the city, but they didn't arrive for almost two hours. Several more fires broke out in the city, with no definite cause. Arson cannot be ruled out, but neither can the possibility of inadequately extinguished cotton bales from earlier in the day, brought back to life by the wind that by now approached gale strength. The tipping point came around 8 p.m. when a fire started on Richardson Street. There is no conclusive evidence that establishes how it began, but it roared for several hours and caused most of Columbia's destruction. The fire ended only because the wind ended around 3 a.m., allowing firefighting efforts to finally succeed." ("Was the Burning of Columbia, S.C. a War Crime?" By Thom Bassett) One of the key features of Sack and Destruction is the extensive, street-by-street list of property destroyed during Sherman's occupation of Columbia. His record of burned buildings constitutes the most authoritative information available on the extent of the damage. Pages 58-76 offers a list the property destroyed. Previous owner's name neatly written at top of front free fly leaf else very good plus.

Inventory Number: 50745

![Romance And Dim Trails. A History Of Clay County DOUTHITT, KATHERINE CHRISTIAN (MRS J. W. [EDITOR-IN CHIEF]](/media/images/thumb/53188.jpg)